Peer Reviewed Articles the Effects of Exercise on Depression

- Review

- Open up Access

- Published:

Systematic review and meta-analysis of the furnishings of practise on depression in adolescents

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 16, Article number:16 (2022) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Low is widespread among adolescents and seriously endangers their quality of life and academic operation. Developing strategies for adolescent low has of import public wellness implications. No systematic review on the effectiveness of physical exercise for adolescents aged 12–18 years with depression or depressive symptoms has previously been conducted. This written report aims to systematically evaluate the effect of concrete exercise on adolescent depression in the hope of developing optimum physical practise programs.

Methods

Nine major databases at home and abroad were searched to remember randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on exercise interventions amongst adolescents with low or depressive symptoms. The retrieval period started from the founding date of each database to May one, 2021. The methodological quality of the included articles was evaluated using the modified PEDro scale. A meta-assay, subgroup assay, sensitivity analysis, and publication bias tests were then conducted.

Results

Fifteen articles, involving xix comparisons, with a sample size of 1331, were included. Physical practice significantly reduced adolescent low (standardized mean difference [SMD] = − 0.64, 95% CI − 0.89, − 0.39, p < 0.01), with a moderate consequence size, in both adolescents with low (SMD = -0.57, 95% CI − 0.ninety, − 0.23, p < 0.01) and adolescents with depressive symptoms (SMD = − 0.67, 95% CI − 1.00, − 0.33, p < 0.01). In subgroups of different depression categories (low or depressive symptoms), aerobic do was the main class of exercise for the handling of adolescents with depression. For adolescents with depression, interventions lasting half-dozen weeks, thirty min/fourth dimension, and 4 times/week had optimum results. The effects of aerobic exercise and resistance + aerobic exercise in the subgroup of adolescents with depressive symptoms were significant, while the consequence of physical and mental exercise (yoga) was not pregnant. For adolescents with depressive symptoms, aerobic exercise lasting 8 weeks, 75–120 min/fourth dimension, and iii times/week had optimum results. Physical practise with moderate intensity is a better choice for adolescents with depression and depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Physical exercise has a positive effect on the comeback of depression in adolescents.

The protocol for this written report was registered with INPLASY (202170013). DOI number is ten.37766/inplasy2021.7.0013. Registration Engagement:2021.vii.06.

Background

The mental health of adolescents has get an increasingly serious public health trouble worldwide [ane]. Depression is a common mental illness in adolescents, with a prevalence of about four.v% [ii]. Low seriously endangers adolescents' physical and mental wellness, academic performance, and interpersonal relationships [3]. In severe cases, these adolescents may even commit suicide [iv]. In contempo years, the incidence of low in Mainland china has continued to rise, and adolescents business relationship for a prominent proportion of patients in the dispensary [5, 6]. When adolescents with depressive symptoms or negative emotions do non receive timely intervention, they risk developing depression [7]. On Baronial 31, 2020, China'southward National Health Commission released the "Working Programme for Exploring Special Services for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression" [eight]. The programme stated that high schools should add depression screening to pupil health examinations, as results show that many students accept depressive symptoms. Effective strategies to reduce depressive symptoms in adolescents are needed.

The consequence of do on depression has become a research hotspot in recent years [ix, x]. Cantankerous-sectional studies over the past thirty years accept suggested that low physical activity is an important risk factor for the evolution of depression [eleven, 12]. Prospective cohort studies have suggested that regular exercise reduces the run a risk of developing depression [13, xiv]. Man and animal experiments showed that exercise tin can exert an antidepressant effect past increasing mitochondrial activity in encephalon neurons, stimulating the secretion of monoamine neurotransmitters, increasing the concentration of neurotrophic factors, inhibiting the overexpression of inflammatory factors, and regulating the expression of microRNAs [fifteen]. It tin can also reduce depressive symptoms past improving self-efficacy, reducing negative emotions, and stimulating positive behaviors in depressed patients [16]. RCTs have also shown that structured exercise programs tin can finer alleviate depressive symptoms, and there is a dose–response human relationship [17, 18]. Studies have found that moderate- and high-intensity physical exercise tin take a positive effect in the treatment of balmy and moderate depression [19]. For adults, depression is usually regarded as the mental health trouble well-nigh likely to be positively affected past exercise [20].

Antidepressant medication may exist associated with side effects such as weight proceeds, slumber disturbance, and reproductive dysfunction which can be disturbing for adolescents [21]. Psychotherapy is more resources-intensive and is associated with perceived stigma from attending the therapist [22]. Comparatively, physical exercise is more cost-effective. It is convenient to implement inside the community and can potentially accept wider reach and participation [23]. At that place is less inquiry on exercise interventions to care for depression in adolescents compared to adults, especially examining the moderating furnishings of practice-related variables (e.k., exercise type, practise program duration, practise session elapsing, exercise intensity, and exercise frequency) [24]. Although RCTs in children and immature people have shown that physical exercise can relieve low and depressive symptoms [25, 26], the dose–response relationship remains unclear. Given this, this study aimed to systematically summarize the effect of physical do on adolescent depression and to clarify the dose–response relationship betwixt physical do and depressive symptoms in adolescents.

Methods

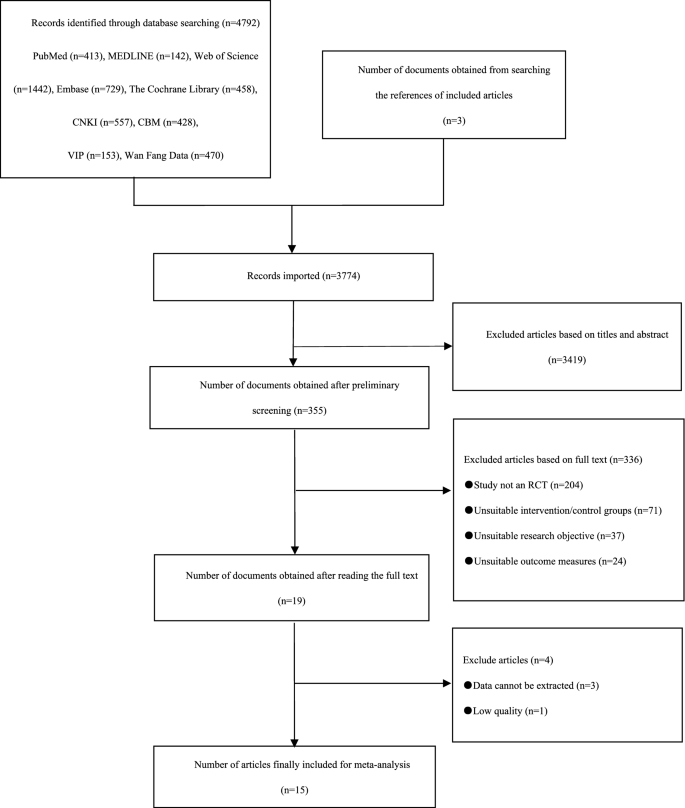

The written report adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (Fig. 1) [27].

Article screening menstruation chart

Inclusion criteria

Based on the PICOS (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design) process used in testify-based medicine [28], the inclusion criteria were equally follows: (i) Participants: adolescents anile 12–xviii diagnosed with depression (based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-IV/5] or International Nomenclature of Diseases [ICD-10]) or assessed to have depressive symptoms. (2) Intervention: the experiment grouping received a structured exercise programme (aerobic exercise, resistance + aerobic exercise, or physical and mental exercise such as yoga [29]) compared with the control group [30]; if at that place were multiple experimental groups in the study, but the group with exercise intervention was included; if there had been multiple independent experiment groups in the aforementioned commodity, it was counted as multiple independent comparisons every bit well. (3) Comparison: The control group had no exercise intervention. (4) Outcomes: An internationally recognized depressive symptom-related scale was used, and its score was used as the study consequence. (5) Report blueprint: randomized controlled trials (RCTs); original peer-reviewed Chinese or English papers.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Participants: Any identified physical or non-depressive mental illness (such as cancer, diabetes, overweight/obesity, or anxiety disorders). Studies which did not provide any data on the participants' characteristics were excluded. (2) Interventions: Employ of combined interventions, such every bit exercise combined with music therapy or cerebral preparation; lack of description of the physical exercise in the intervention pattern (type; plan duration; session duration; intensity; or frequency). (iii) Comparisons: Lack of a command group or control interventions that significantly increased cardiovascular action. (iv) Outcome Measures: Depressive symptom scores not evaluated pre- and post-intervention; Data could not be extracted or original information could not be obtained past contacting the corresponding writer. (5) Study design: Scores on the modified PEDro calibration of less than 4.

Literature retrieval strategy

Nine databases were searched, comprising PubMed, Spider web of Science, The Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, China National Cognition Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), VIP database, and Wanfang Database. The search was conducted from database inception to May 1, 2021.

The search strategy involved a combination of subject terms and free words, and was finalized subsequently repeated checks. Chinese search terms included: adolescents, inferior loftier school students, high school students; exercise, aerobic practise, resistance exercise, high-intensity interval, physical and mental exercise, yoga, dance, aerobics, running, walking; depression, depression symptoms, depressive symptoms, negative emotions; randomized controlled trials. As an instance of the English search terms, the PubMed search strategy was equally follows:

#1 Adolescent [MeSH Terms] OR Adolescents [Title/Abstract] OR Adolescence [Title/Abstract] OR Teenager [Title/Abstruse] OR Teenagers [Title/Abstruse] OR Teen [Title/Abstract] OR Teens [Championship/Abstract] OR Youth [Championship/Abstruse] OR Youths [Title/Abstract];

#2 Do [MeSH Terms] OR Exercise [Title/Abstract] OR Aerobic Exercise [Title/Abstruse] OR Resistance Practice [Championship/Abstract] OR Loftier-Intensity Interval Grooming [Title/Abstruse] OR Heed–Trunk Practise [Title/Abstract];

#3 Depression [MeSH Terms] OR Depressive Disorder [Title/Abstract] OR Depressive Symptom [Title/Abstract] OR Emotional Depression [Title/Abstract] OR Negative Emotion [Title/Abstract];

#4 randomized controlled trial [MeSH Terms].

#5 #1 and #2 and #3 and #4.

Literature screening, data extraction, and quality evaluation

Literature screening

EndNote X9 software was used to remove the duplicates from the search results. Thereafter, two authors (both of whom were experienced researchers in the field) independently screened the literature co-ordinate to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. First, the titles and abstracts were read to preliminarily screen the articles, and the articles that did not see the inclusion and exclusion criteria were deleted and recorded. 2d, the full text of the remaining manufactures was downloaded, read, and reviewed to re-screen the articles. If there was a disagreement between both authors, a 3rd author would review and determine whether to include the study.

Information extraction

Two authors used a pre-designed data extraction form to extract the post-obit information and record information technology: (ane) Basic article information: get-go author's name, written report country, and yr of publication. (two) Basic data: depression type (depression or depressive symptoms), age, sex ratio, and sample size. (3) Physical exercise variable (e.g., practice type, practise program elapsing, exercise session elapsing, do intensity, and exercise frequency).

Quality evaluation

Two authors used a modified version of the PEDro scale [31] to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies. If there was a disagreement, a third writer evaluated the outcome, which was discussed until a consensus was reached. The 10 items on the calibration include "eligibility criteria", "random allocation", "allocation concealment", "baseline similarity between groups", "exercise intensity control", "blinded outcome evaluation", and "dropout charge per unit < fifteen%", "intention-to-treat analysis", "Statistical analysis comparing groups", "point and variability measures". If the relevant standard was clearly met, the particular was scored as 1 point; if the relevant standard was non clearly met or not mentioned, the item was scored equally 0. The highest score that could exist accomplished was ten points, and then < four, four–5, half dozen–8, and 9–10 indicated low, medium, good, and high quality, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The statistical assay was conducted in Stata xvi.0 software. The issue variables were continuous, and hateful ± standard deviations (SD) were extracted for each included comparison. There were no meaning differences in the result variables between the groups in each comparison at baseline. At the end of the experiment, we chose scale scores of both the intervention group and the control group as the event size, which reflects the intervention upshot. Due to the use of multiple depression scales amidst the included manufactures, standardized mean difference (SMD) was used every bit the upshot size for assay, with 0.2, 0.v, and 0.viii indicating small, moderate, and large effect sizes, respectively [32]. Heterogeneity was quantified by Itwo (with 75%, 50%, and 25% indicating loftier, medium, and low degrees of inter-study heterogeneity, respectively [33]) and Cochran'south Q test p value. If there is publication bias among the included articles, the trim and fill method was used to correct for asymmetry.

Results

Literature retrieval results

Equally shown in Fig. 1, a total of 4792 articles were obtained by searching PubMed (north = 413), MEDLINE (due north = 142), Web of Science (n = 1442), Embase (northward = 729), The Cochrane Library (northward = 458), CNKI (n = 557), CBM (n = 428), VIP database (due north = 153), and Wanfang Database (north = 470). Additionally, three manufactures were obtained past searching the references of the included articles. After deduplication, 3774 manufactures were obtained. After preliminary screening, 355 articles were obtained. After re-screening the articles by reading the full texts and excluding articles due to unsuitable study pattern (not an RCT) intervention/control groups, research objective, or outcome measures, xix articles were obtained. Subsequently excluding articles with unavailable information or depression-quality articles, 15 articles were included in the meta-analysis.

Characteristics of included literature

Every bit shown in Table one, 15 articles were included, with 19 comparisons. The publication year was 1982 to 2017. There were 1331 participants, ranging from 24 to 209 per commodity. The mean historic period of the participants was 15.90 ± 1.23 years old. The comparisons were conducted in 8 countries: the United States (n = viii) [34,35,36,37,38,39,xl], Iran (n = iii) [41, 42], Germany (northward = 2) [43], Australia (n = 2) [44], the Britain (north = i) [45], Republic of korea (north = 1) [46], Chile (n = 1) [47], and Colombia (northward = 1) [48]. Regarding depression type, 6 comparisons were on depression and 13 were on depressive symptoms. Regarding recruitment, 9 comparisons involved participants recruited from the following special organizations: inpatient section (n = 3), mental health eye (north = 2), community outpatient clinic (north = 1), juvenile detention center (n = 2), and school for young offenders (n = 1). Additionally, 10 comparisons involved exercise interventions carried out in school (5 in junior loftier school and 5 in high school).

The exercise programs mainly involved aerobic practice, resistance + aerobic practise, or yoga (though 1 article involved whole-body muscle vibration). The total exercise program elapsing for adolescents with depression ranged from half-dozen to 12 weeks, the exercise session duration ranged from 30 to 45 min, exercise intensity was moderate intensity (1 comparison) and optional intensity (1 comparing), and the practise frequency ranged from 3 to iv times per week. The total practice programme duration for adolescents with depressive symptoms ranged from 6 to twoscore weeks, the practise session elapsing ranged from 8 to 120 min, exercise intensity was moderate intensity (2 comparisons) and cocky-selected intensity (two comparisons), and the frequency ranged from two to three times per week.

Nine comparisons (depression: 3; depressive symptoms: six) showed that there was no significant difference in depression scores betwixt the do and control groups at the end of the report, while ten comparisons (depression: iii; depressive symptoms: 7) showed significant differences. Five comparisons (low: 4; depressive symptoms: 1) included a follow-up period after the experiment. Ii of these comparisons (depression: 1; depressive symptoms: ane) showed that the depression scores during the follow-up period were not significantly different between the exercise and control groups, while 3 comparisons (depression: 3) showed significant differences. There were no adverse events amidst the included studies. The mean dropout charge per unit of the practise grouping was 8.33% and that of the control group was 9.21%, with no meaning deviation (t = -0.18, p = 0.86).

Methodological quality evaluation

Every bit shown in Table 2, the PEDro score among the 15 included manufactures was 5–viii points. There were 4 medium and 11 high-quality articles, with a mean of 6 points. The overall research quality was good. All articles mentioned "eligibility criteria", "random allocation", "baseline similarity betwixt groups", "statistical assay comparison groups", and "point and variability measures". Additionally, 4 articles mentioned "exercise intensity control", 1 article mentioned "blinded consequence evaluation", ii articles mentioned using "intention-to-care for analysis", and 7 manufactures mentioned "dropout rate < 15%" (Table 2).

Meta-analysis of the impact of exercise on depression in adolescents

Meta-analysis results

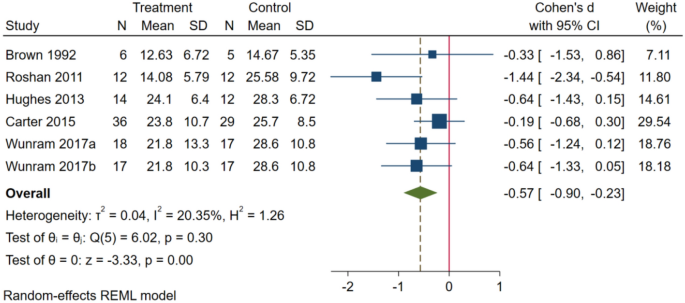

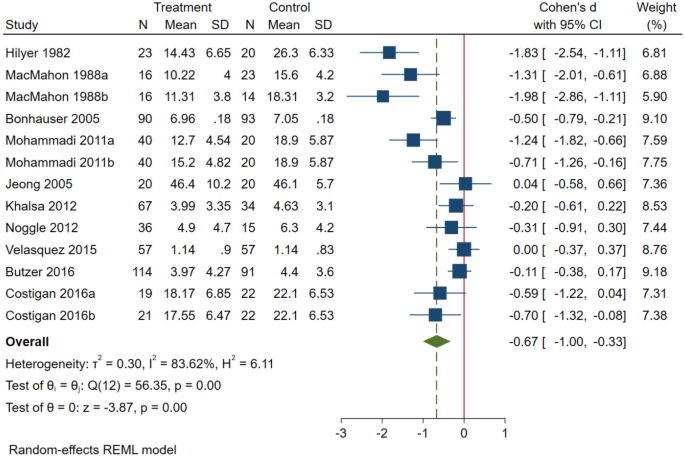

A full of 19 studies included I2 = 75.05%, combined result size SMD = − 0.64, 95% CI (− 0.89, − 0.39, P < 0.01). The results showed that post-intervention, subjects in the intervention group showed more than meaning reduction in depressive symptoms than the control grouping, with a moderate effect size. As shown in Fig. 2, adolescents with depression I2 = 20.35%, combined effect size SMD = -0.57, 95% CI (− 0.90, − 0.23, P < 0.01), there is low heterogeneity. Every bit shown in Fig. iii, adolescents with depressive symptoms Itwo = 83.62%, combined effect size SMD = − 0.67, 95% CI (− 0.90, − 0.23), P < 0.01, in that location is a high degree of heterogeneity.

Wood plot of the effect of exercise on adolescents with depression

Wood plot of the effect of practice on adolescents with depressive symptoms

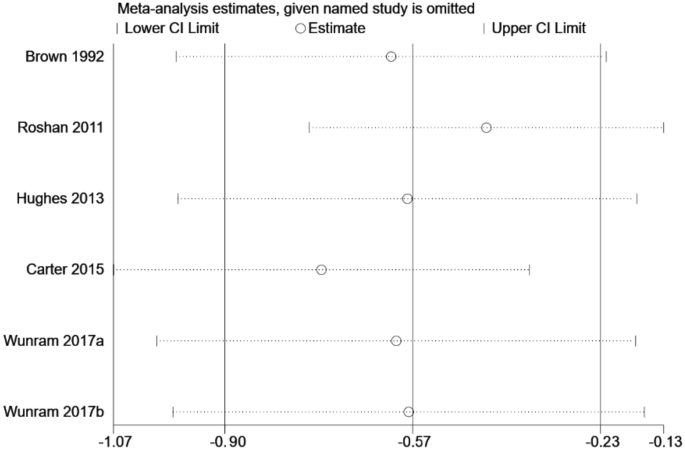

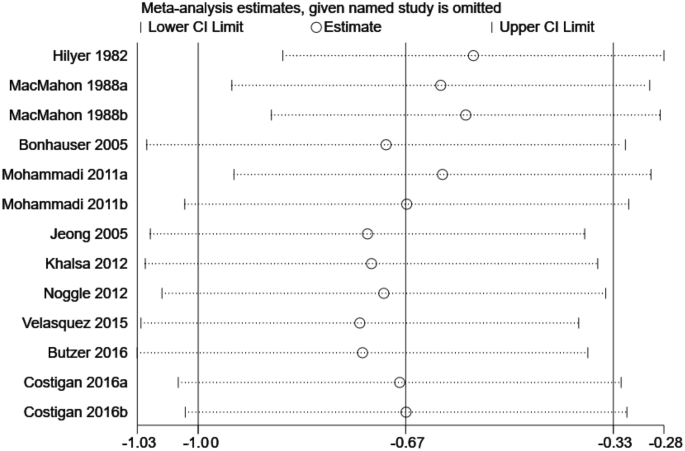

Sensitivity analysis

In guild to explore whether the heterogeneity between studies is caused by a single report, Stata sixteen.0 software was used for sensitivity analysis [49]. As shown in Figs. four and five, the effect size of the depression group and the depressive symptom group were not significantly changed later eliminating single studies one past ane, indicating that the report results were relatively stable.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of exercise on depression in adolescents

Sensitivity assay of the effect of exercise on depressive symptoms in adolescents

Subgroup assay

As shown in Tabular array three, to further explore the source of heterogeneity, a subgroup analysis of potential moderating variables was performed. Regarding do type, the issue of aerobic practice amongst adolescents with depression was pregnant. The effects of aerobic exercise and resistance + aerobic exercise amid adolescents with depressive symptoms were also significant, while the outcome of yoga was not pregnant. There was a high degree of heterogeneity in the aerobic practice and resistance + aerobic practice subgroups among adolescents with depressive symptoms. Regarding program elapsing, the effect of continuous intervention for 6 weeks in adolescents with low was significant, while the effect of continuous intervention for 9–12 weeks was not significant. For adolescents with depression symptoms, the upshot of continuous intervention for 8 weeks was significant, while the effects of continuous intervention for ten–12 and > 12 weeks were non pregnant. At that place was a loftier degree of heterogeneity in the > 8-week subgroup among adolescents with depressive symptoms. Regarding do session elapsing, the effect of 30 min of exercise in adolescents with depression was pregnant, while 45 min was non significant. For adolescents with depressive symptoms, the effect of 75–120 min was meaning, but the effect of xxx–45 min was not meaning. In that location was a high degree of heterogeneity in the xxx–45 and 75–120 min subgroups among adolescents with depressive symptoms. Regarding exercise frequency, 3–4 times/week amongst adolescents with depression was significant, and four times/calendar week was better. The effect of 3 times/week in adolescents with depressive symptoms was meaning, while ii times/week was non. The effect of exercise 3 times/calendar week amid adolescents with depressive symptoms was highly heterogeneous. Moderate and loftier intensity practise had a meaning effect on depressive symptoms amongst adolescents with moderate intensity interventions producing the greater do good.

Publication bias

The Egger regression method was used to assess publication bias regarding the included articles [50]. Egger'southward test results showed that at that place was no publication bias in the depression group (t = − one.42, P = 0.23, 95% CI − 6.45, 2.09). In the depressive symptom group, the result showed likelihood of publication bias (t = − three.12, P = 0.01, 95% CI − half-dozen.87, − i.xix). The reason for publication bias is that more positive results than negative results were included [51]. The trim and fill method [52] was used to identify and correct the disproportion caused by publication bias. The results testify that no sample needed to be corrected or recalculated amongst the experimental samples. The random-effects model calculates the indicate estimate of the combined RR and 95% CI was − 0.65 (− 0.87, -0.58) after trim-and-fill, and the effect size RR deviation before and after trim-and-fill up did not change significantly, suggesting that publication bias has piddling upshot on the results, and the meta-analysis results are relatively robust.

Give-and-take

This study showed that practice has a moderate consequence on alleviating depressive symptoms in adolescents, which is consistent with the results from a previous meta-assay [53]. A previous meta-analysis on the utilize of exercise to treat depression in children and adolescents too showed that practise had a small-to-moderate effect [21], but due to the heterogeneity among the patients, the authors stated that there was insufficient testify to prove the benefits of exercise. Additionally, two meta-analyses of young people (4–25 years old) found that exercise has a moderate-to-large effect [54, 55]. All the same, in addition to RCTs, these two meta-analyses included quasi-experimental and observational studies, and the overall methodological quality was low. In addition, previous meta-analyses covered participants with a wide range of ages [21, 50, 51]. Given the biological and psychological differences between children and adolescents [56], this may have had a confusing effect on the summary results. Therefore, unlike these previous meta-analyses, our meta-assay only included adolescents aged 12–18 years who had been diagnosed with depression or had been assessed to have significant depressive symptoms. Nosotros besides excluded studies which recruited individuals with comorbid diseases closely related to depression. Furthermore, we explored the moderating effects of practice-related variables in social club to better assess the dose–response relationship of exercise. The sensitivity analysis and publication bias test suggested that the results were highly stable.

In this meta-assay, 5 comparisons involved follow-up results, 3 of which suggested that exercise had a sustained do good (at about half dozen months) later on the intervention. First, Carter et al. found that the depressive symptoms at week 24 in the 6-week aerobics exercise group were significantly lower than those in the control group [41]. 2nd, the two comparisons by Wunram et al. (one involving aerobic do and the other involving whole-trunk muscle vibration) both found that at that place was a significant departure at calendar week 26 in depression scores between the exercise and command groups. The depression remission rate in both the exercise groups (67.eight%) was significantly higher than that in the control group (26.8%) [39]. The authors explained that this may be related to the participants maintaining regular exercise after the intervention [57]. Due to the limited number of follow-up studies, short timeframes, and lack of continuous measurement, larger follow-upwards studies are notwithstanding needed to farther explore the sustainability of the effectiveness of exercise interventions to reduce depression in adolescents.

In addition, enquiry has shown that 80% of depressed adolescents refuse to be treated once more due to side effects or stigma afterwards the first psychological or drug treatment [58]. In contrast, none of our included articles reported any agin events during the interventions. A meta-assay of the effectiveness of treatment for low in adolescents establish that the dropout rates regarding psychological and drug therapy amid adolescents were approximately 23% and 45%, respectively [59]. In dissimilarity, in our meta-analysis, the hateful dropout rates were 8.33% and 9.21% in the exercise and command groups, respectively, with no significant difference (t = − 0.eighteen, p = 0.86). Given that practice has similar benefits to psychological and drug therapy, the high compliance amidst adolescents with exercise, and the many benefits of practise in the growth and development stages [sixty], the apply of exercise to prevent and treat depression in adolescents is feasible and acceptable.

At nowadays, most studies report that the crusade of depression is related to the dysfunction of neurotransmitters such as serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), dopamine, and norepinephrine [61]. In rats, pond exercises over ten weeks significantly increased the levels of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the hippocampus [62]. Voluntary running exercises for 8 weeks significantly increased the levels of dopamine and its metabolites in the prefrontal cortex and striatum of rats [63]. Later a half-dozen-week jogging intervention for patients with depression, the plasma levels of gamma-aminobutyric acrid (GABA) increased and the depression symptoms decreased [64]. Six months of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise significantly increased the prefrontal cortex gray matter volume in patients with depression (decreased gray affair volume is a central physiological sign of depression [65]), which was direct proportional to the amount of exercise [66]. In addition, exercise among patients with depression upregulated encephalon-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which stimulates and mediates neurogenesis and regulates depressive behavior [67], in the hippocampus and cortex, promoted hippocampal neurogenesis, and significantly enhanced synaptic plasticity [68]. In improver, exercise alleviated hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal feedback regulation obstacles by modulating cortisol and IL-6 levels, and thereby improved depression [69].

Current enquiry mostly indicates that for people with depressive symptoms, physical do is as effective every bit antidepressant drugs and psychotherapy and, for patients with depression, exercise can be used as a supplement to traditional therapy [70,71,72]. Walking every day for 10 days, with an 80% maximum middle charge per unit (HRmax), significantly reduced the Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Scale (BRMS) score of patients with major depression [73]. Cycling at 70–80% HRmax for 12 weeks reduced the symptoms of individuals with depressive symptoms, and improved maximum oxygen uptake and visuospatial memory [74]. Aerobic exercises in physical education classes significantly reduced adolescents' impulsivity, anxiety, drug corruption [36, 38]. Studies have found that the effect of physical practise on low is influenced past the severity of low, and is significantly negatively correlated with the level of depression [75, 76]. This is considering patients with depression usually accept a depression mood for more than 2 weeks, which is accompanied by a decrease in hippocampus volume, structural changes in the prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, and temporal lobe, as well as cognitive dysfunction [77]. The symptoms of general depression are ordinarily mild, often manifested as lack of happiness, low cocky-esteem, pessimism, loneliness, and other negative emotions [78]. A single exercise session amid individuals with depressive symptoms can significantly better self-efficacy, thereby reducing negative emotions [79], while regular exercise for > iii months tin effectively reshape the central nervous organization organization of patients with depression [80]. Participants' concrete health may also be an of import factor affecting the effectiveness of the intervention. Adolescents with mental or physical diseases such as obesity [81], chronic fatigue syndrome [82], attending deficit hyperactivity disorder [83], may differ from ordinary adolescents in their exercise tolerance. They are more likely to adhere to moderate- than to high-intensity do [84].

Exercise blazon may be the moderating factor that affects the effect of the intervention. At nowadays, aerobic exercise is the most important type of practise to treat depression [85]. Aerobic exercise increases the levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-one) in the mouse brain, and increases the volume of the subventricular and subgranular zones in the hippocampal dentate gyrus, promoting the differentiation of hippocampal neurons [86]. In addition, aerobic exercise activates central nervous system neuroactive substances and BDNF in the brain [87]. Jeong et al. institute that 12 weeks of aerobic dance in adolescents increased the plasma concentration of serotonin and decreased the concentration of dopamine, suggesting that the stability of the sympathetic nervous system increased [42]. Roshan et al. establish that 6 weeks of aerobic walking in water significantly increased the 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) sulfate value in the urine of adolescents, and it was significantly negatively correlated with the HAMD score, suggesting that aerobic exercise reduced depressive symptoms in adolescents [37]. In add-on, compared with aerobic exercise solitary, resistance + aerobic exercise can produce complementary neurobiological and other physiological furnishings [88]. Regarding the ii resistance + aerobic exercises included in our meta-analysis, Hilyer et al. institute that the BDI score was significantly lower after a 20-week resistance + aerobic practice program than that of the control grouping [32]. 2nd, Costigan et al. found that resistance + aerobic exercise slightly improved subjective well-being among adolescents, but not depressive symptoms [xl]. As our meta-analysis merely included 2 articles on resistance + aerobic exercise, its effect on depression in adolescents needs to be verified by multiple boosted RCTs. In addition, due to the inherent listlessness of patients with major depression, it is sometimes hard to motivate them to take agile exercise[89]. Whole-body muscle vibration preparation was chosen as an auxiliary or supplementary exercise method. This kind of practice tin be performed on a high level of physical action fifty-fifty with a low motivation to do[90]. Hyperactive HPA axis in patients with major depression is one of the important reasons for its onset[91]. In that location is some evidence that whole-body musculus vibration training tin can have a positive consequence on maintaining stable cortisol secretion in adolescents with severe depression and reducing the activity of the HPA [43]. Due to the limited number of studies in this literature, vibration training currently needs stronger empirical evidence to investigate the furnishings of this approach in alleviating depression in adolescents.

In addition, our meta-analysis constitute that yoga did not significantly impact depression in adolescents. Yoga, every bit a concrete and mental exercise based on body posture exercises, has been found to reduce anxiety and stress [92]. Yoga can improve negative emotions past regulating the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis and sympathetic nervous organization, increasing thalamic GABA levels and reducing cortisol levels [93]. Of the four included yoga manufactures (satyananda yoga:1; kripalu yoga:2; cocky-designed yoga:1), only 1 report has a significant difference compared to the control group. Although these studies mentioned the type of yoga selected, they did not describe the specific intervention details during the implementation process. We tin can just roughly know that yoga elements include posture, breathing, relaxation and meditation. Amid them, Kripalu Yoga is oft described as "dynamic meditation"[94]. During practice, students need to pay more attention to the individual psychological feelings brought by yoga postures[95]. Therefore, students are required to maintain a gentle and introspective attitude throughout the practise. Each pose of Kripalu Yoga needs to be maintained for a long time in order to fully release the pent-up emotions[96]. Kripalu Yoga has achieved significant intervention effects in one study, which may be related to its accent on obeying the wisdom of the torso[40]. The reason for the insignificant effect of yoga intervention may prevarication in the characteristics of yoga exercise, the duration of yoga experiment and experiment control. Adolescent males oftentimes resist participating in low-intensity exercise such as yoga and tend to choose more intense exercise types, then gender factors may impact the issue of yoga interventions [97]. For male students who practise not similar yoga, they would choose to use the word "active" to describe the purpose they desire to pursue in their physical practise. In yoga exercises, they feel more than restrained [98]. As a complementary therapy for physical and psychological disorders, yoga has been extensively studied in adults [99]. Long-term follow-upward showed that yoga led to delayed transformation, leading to improvement in long-term cocky-control in emotion, though the brusk-term upshot was non pregnant [36]. In addition, the current practice of yoga among young people may limit its effectiveness due to the lack of specific standards for quality control of yoga implementation. Longer mail service-intervention follow-upward studies on yoga interventions should be conducted, and the implementation processes should exist conspicuously reported, so every bit to provide the best advice for young people on using yoga to relieve depression.

Exercise programme duration, session elapsing, frequency, and intensity may moderate the effects of exercise. 1 study showed that there is an inverted U-shaped human relationship between the exercise program duration and mental wellness symptom relief in adolescents [100]. Another report showed that maintaining regular practise for 6–eight weeks significantly reduced negative emotions in adolescents, but with the prolongation of the programme, the benefits did non significantly improve [101]. International public health concrete activity guidelines stipulate that at to the lowest degree 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise should be performed every week to maintain wellness [102]. Normally, there is a positive dose–response relationships between exercise duration/frequency and depressive symptoms improvement [103]. In depressed rats, a unmarried 30-min session of cycle running reduced the serum corticosterone concentration compared to twenty min [104]. In add-on, 8-week high-frequency (3–five sessions/week) aerobic do significantly increased serotonin and amygdala norepinephrine in the hippocampus of the encephalon of patients with depression compared to low-frequency (1 session/calendar week) aerobic exercise [105]. Moreover, loftier-frequency exercise accelerated the serum BDNF acme, which promoted adaptation of cardinal neurotransmitter release and was more constructive at reducing depressive symptoms [106]. For adolescents, the shorter the effective fourth dimension of physical exercise, the easier it is to improve the motivation of the adolescents to participate in physical do [107]. Reduced energy level is a characteristic symptom in depressed patients, and long-term continuous practice may be too enervating for them. Furthermore, a meta-analysis on practice durations/frequencies showed that exercise that lasted ≤ 45 min/session reduced depression symptoms more than than > 45 min/session, and ≥ 4 sessions/calendar week had a greater effect than 2–3 sessions/calendar week [108].

In add-on, at that place are a total of half dozen comparisons in this article detailing the control of exercise intensity in the experiment. For adolescents with depression, moderate intensity and self-selected intensity may be meliorate exercise options for them. Since but one comparison of each level of intensity was identified, further experiments are needed to strengthen any specific conclusions that can exist fatigued. For adolescents with depressive symptoms, a subgroup assay found that moderate intensity and loftier intensity have a proficient effect on reducing their depressive symptoms. Previous research showed that moderate- and loftier-intensity exercise has a stronger effect on low than low-intensity practice [109]. The American Sports Medicine Association recommends 60–80% HRmax intensity to treat depression [110]. Exercise intensity is positively associated with BDNF and plasma endorphin release [111]. Yet, ane report found that compared to high-intensity interval training, moderate-intensity continuous aerobic exercise reduced the levels of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-half dozen, and IL-1β [112]. Given the depression self-esteem and self-efficacy of depressed patients, moderate-intensity exercise is currently used more frequently [113]. Compared to cocky-selected intensity, exercise at a prescribed intensity usually leads to a poorer emotional experience [114]. The single included commodity on self-selected exercise intensity amid adolescents with severe depression found that there was no meaning difference in depression scores between the exercise and control groups later 6 weeks of intervention, but the exercise grouping had a significantly higher improvement at the half-dozen-calendar month follow-up. Farther studies to examine the effectiveness of self-selected physical activeness intensity on depression in adolescents are needed. As the suitable exercise intensity differs between adolescents and adults, information technology is necessary to further explore the effect and acceptability of unlike intensities on depression in adolescents in order to find the optimum intensity.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. (1) Merely published Chinese and English language articles were included, so the comprehensiveness of the search was express. (2) Just two of the included articles fully described allotment concealment and only one mentioned blinded outcome assessment. (3) All the articles used subjective self-reported outcomes, with a lack of objective evaluation (such as biomarkers). (4) There was a high degree of heterogeneity amongst the studies of adolescents with depressive symptoms. (5) There was a lack of uniform standards and controls for exercise intensity variables. (6) The physical activity level of the subjects may affect the intervention consequence, while this variable was not establish or included when compiling relevant data. (7) The optimal exercise program in this research was based on the summary of current evidence. More RCTs are needed in the future to further discuss the intervention furnishings of dissimilar variables.

Conclusion

This study shows that concrete exercise, every bit an culling or complementary handling, has a positive result on alleviating depression in adolescents, with a moderate issue size. Based on the current bear witness, for adolescents with depression lasting for 6 weeks, a physical practice plan of 30 min/time, 4 times/week, and aerobic exercise is better. For adolescents with depressive symptoms lasting for 8 weeks, 75–120 min/time of practise 3 times/week, and aerobic exercise is better. Concrete practise of moderate intensity is a meliorate option for adolescents with depression and depressive symptoms. In the hereafter, empirical research should involve long-term, high-quality RCTs, and increased follow-up to explore the sustained benefits of physical exercise. The forms of do intervention among adolescents should be farther enriched, and the control of the intensity of physical exercise should be strengthened as well.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the electric current study are available from the corresponding writer on reasonable asking.

References

-

Potrebny T, Wiium N, Lundegard MM. Temporal trends in adolescents' cocky reported psychosomatic health complaints from 1980–2016: a systematic review and meta-assay. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(eleven):e0188374.

-

Li J, Liang J, Qian S. Depressive symptoms among children and adolescents in Communist china: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7459–70.

-

Hawton Grand, Saunders K, O'Connor RC. Cocky-damage and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–82.

-

Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet. 2018;392:2299–312.

-

Li JL, Chen X, Zhao CH. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Chinese children and adolescents. Chin J Child Wellness. 2016;24(3):295–8.

-

Liu FR, Song XQ, Shang XQ. A meta-assay of the detection charge per unit of depressive symptoms in middle school students. Mentum Ment Health J. 2020;34(2):123–8.

-

Rutter M, Kim-Cohen J, Maughan B. Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and developed life[J]. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;47(3–iv):276–95.

-

General Office of National Wellness Commission of the People'due south Republic of Mainland china. Working program for exploring special services for the prevention and treatment of depression. General Office of National Health Commission of the People's Commonwealth of China. 2020. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s7914/202009/a63d8f82eb53451f97217bef0962b98f.shtml. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

-

Ormel J, Cuijpers P, Jorm AF, Schoevers R. Prevention of depression will only succeed when it is structurally embedded and targets big determinants. Globe Psychiatry. 2019;eight:111–2.

-

Chen M, Zhang XB, Luo YZ, et al. Research progress on neurobiological related mechanisms of practice to improve depression. Prc Sports Technol. 2021;57(4):89–97.

-

Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Schuch FB, Firth J, Rosenbaum South, Veronese N, Solmi Grand, Mugisha J, Vancampfort D. Concrete activity and low: a large cross-sectional, population-based study across 36 low- and middle-income countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;134(vi):1–11.

-

Mc Dowell CP, Carlin A, Capranica L, Dillon C, Harrington JM, Lakerveld J, Loyen A, Ling FCM, Brug J, MacDonncha C, Herring MP. Associations of self-reported physical activity and depression in 10,000 Irish adults across harmonised datasets: a DEDIPAC-study. BMC Public Health. 2018;xviii:779–88.

-

Mammen G, Faulkner G. Physical action and the prevention of depression: a systematic review of prospective studies. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(5):649–57.

-

Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Practice as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:42–51.

-

Ma K, Liu JM, Fu CY. Research progress on the intervention effect and mechanism of exercise on depression. China Sports Technology. 2020;56(11):thirteen–24.

-

Hu L, Han YQ. The new development of the research on the neurobiological mechanism of sports anti-depression. J Shanxi Norm Univ (Natural Science Edition) 2019;47(3):9–twenty+125.

-

Doose Yard, Reim D, Ziert Y. Self-selected intensity exercise in the treatment of major depression: a businesslike RCT. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015;5:one–19.

-

de Bruin EI, van der Zwan JE, Bögels SM. A RCT Comparing daily mindfulness meditations, biofeedback exercises, and daily physical do on attention command, executive performance, mindful awareness, self-compassion, and worrying in stressed immature adults. Mindfulness. 2016;half dozen:1–xi.

-

Nystrom MBT, Neely G, Hassmén P, et al. Treating major depression with physical activity: a systematic overview with recommendations. Cogn Behav Ther. 2015;44(4):341–52.

-

Malcom Eastward, Evans-Lacko Due south, Little K, Henderson C, Thornicroft M. The impact of exercise projects to promote mental wellbeing. J Ment Wellness. 2013;22(vi):519–27.

-

Jin C, Gao C, Chen C, et al. A preliminary report of the dysregulation of the resting networks in first-episode medication-naive adolescent low. Neurosci Lett. 2011;503(2):105–9.

-

Wang LP, Wang HP. Claiming to traditional therapy: 3 new progresses in psychological treatment of boyish depression. Med Philos. 2019;40(iii):51–4.

-

Li A, Yau Southward, Machado Due south, et al. Enhancement of hippocampal plasticity past physical practise as a polypill for stress and depression: a review. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2019;18(4):294–306.

-

Biddle S, Asare Yard. Concrete action and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:886–95.

-

Larun L, Nordheim LV, Ekeland E, Hagen KB, Heian F. Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;i:one–49.

-

Brown HE, Pearson N, Braithwaite RE, Brown WJ, Biddle SJH. Physical action interventions and depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:195–206.

-

Page One thousand, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;6:1743–9191.

-

Higgins JP, Green South, Scholten RJ. Maintaining reviews: updates, amendments and feedback. In: Higgins JP, Light-green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: cochrane book series. Chichester: Wiley; 2015. p. 31–49.

-

Cai ZD, Lou SJ, Chen AG. Skilful consensus on the dose-consequence relationship of physical do delaying the cognitive decline of the elderly. J Shanghai Sport Univ. 2021;45(i):51–65+77.

-

Budde H, Schwarz R, Velasques B, Ribeiro P, Holzweg Grand, Machado South, Brazaitis One thousand, Staack F, Wegner M. The need for differentiating between exercise, physical action, and training. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;viii:i–3.

-

Ludyga Southward, Gerber M, Brand South, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U. Acute effects of moderate aerobic practice on specific aspects of executive function in different historic period and fitness groups: a meta-analysis. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(11):16–26.

-

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;ii(334):499–500.

-

Wang D, Zhai JX, Mou ZY. Heterogeneity in meta analysis and its treatment methods. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2009;9(ten):1115–8.

-

Chocolate-brown Southward, Welsh MC, Labbé EE, Vitulli WF, Kulkarni P. Aerobic exercise in the psychological treatment of adolescents. Percept Mot Skills. 1992;74:555–60.

-

Hughes CW, Barnes Due south, Barnes C, Defina LF, Nakonezny P, Emslie GJ. Depressed adolescents treated with exercise (Appointment): a airplane pilot randomized controlled trial to test feasibility and establish preliminary effect sizes. Ment Health Phys Act. 2013;6:119–31.

-

Hilyer JC, Wilson DG, Dillon C. Concrete fitness training and counseling equally handling for youthful offenders. J Couns Psychol. 1982;29:292–303.

-

MacMahon JR, Gross RT. Concrete and psychological effects of aerobic practice in delinquent boyish males. Am J Dis Kid. 1988;142:1361–6.

-

Khalsa SBS, Hickey-Schultz L, Cohen D, Steiner N, Cope S. Evaluation of the mental health benefits of yoga in a secondary school: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012;39:eighty–ninety.

-

Noggle JJ, Steiner NJ, Minami T, Khalsa SBS. Benefits of yoga for psychosocial well-existence in a US loftier schoolhouse curriculum: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:193–201.

-

Butzer B, LoRusso A, Shin SH, Khalsa SBS. Evaluation of yoga for preventing boyish substance utilize gamble factors in a middle school setting: a preliminary group-randomized controlled trial. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:603–12.

-

Roshan VD, Pourasghar M, Mohammadian Z. The efficacy of intermittent walking in water on the rate of MHPG sulfate and the severity of depression. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2011;5:26.

-

Mohammadi Thou. A written report and comparison of the result of team sports (soccer and volleyball) and individual sports (tabular array lawn tennis and badminton) on depression among high school students. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2011;5:1005–11.

-

Wunram HL, Hamacher S, Hellmich M, Volk M, Jänicke F, Reinhard F, Bloch Westward, Zimmer P, Graf C, Schönau E, Lehmkuhl K, Bender S, Fricke O. Whole torso vibration added to handling as usual is effective in adolescents with depression: a partly randomized, 3-armed clinical trial in inpatients. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;27(v):645–62.

-

Costigan SA, Eather N, Plotnikoff RC, Hillman CH, Lubans DR. Loftier intensity interval training on cognitive and mental health in adolescents. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:e108–9.

-

Carter T, Guo B, Turner D, Morres I, Khalil E, Brighton Due east, Armstrong Thousand, Callaghan P. Preferred intensity exercise for adolescents receiving treatment for depression: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:247.

-

Jeong YJ, Hong SC, Lee MS, Park MC, Kim YK, Suh CM. Dance movement therapy improves emotional responses and modulates neurohormones in adolescents with mild depression. J Neurochem. 2005;115(12):1711–20.

-

Bonhauser M, Fernandez G, Püschel K, Yañez F, Montero J, Thompson B, Coronado G. Improving physical fitness and emotional well-being in adolescents of low socioeconomic status in Chile: results of a school-based controlled trial. Wellness Promot Int. 2005;2:113–22.

-

Velásquez 1000, Lòpez MA, Quiñonez North, Paba DP. Yoga for the prevention of low, feet, and aggression and the promotion of socio-emotional competencies in school-aged children. Educ Res Eval. 2015;21:407–21.

-

Zhang SH. Meta assay should reasonably set subgroup analysis and sensitivity assay to accurately interpret the results. Chin J Modern Nerv Dis. 2016;16(1):1–2.

-

Yu HQ, Zheng HJ, Li Y, et al. Meta-assay published a study on the method of bias diagnosis. Prc Wellness Stat. 2011;28(4):402–5.

-

Shi XQ, Wang ZZ. Comparison of efficacy differences between Egger's test and Begg'south examination and reason assay. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol (Medical Edition) 2009;38(1):91–iii+102.

-

Zhang TS, Zhong WZ. The realization of not-parametric clipping and compensation method in Stata. Evid Based Med. 2009;9(4):240–ii.

-

Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, Hovland A. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. J Touch Disord. 2016;9:67–86.

-

Pascoe M, Parker A. Concrete action and exercise as a universal depression prevention in immature people: a narrative review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;9:1–7.

-

Radovic S, Gordon M, Melvin G. Should nosotros recommend exercise to adolescents with depressive symptoms? A meta-assay. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;10:1–7.

-

Asante K. Exploring historic period and gender differences in health adventure behaviours and psychological functioning among homeless children and adolescents. Int J Ment Health. 2015;17:278–92.

-

Antunes HK, Leite GS, Lee KS, Barreto AT, Santos RV, Souza Hde Due south, Tufik Southward, de Mello MT. Practice deprivation increases negative mood in exercise-addicted subjects and modifies their biochemical markers. Physiol Behav. 2016;156:182–xc.

-

Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care amongst U.South. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–55.

-

Rohden AI, Benchaya MC, Camargo RS, Moreira TC, Barros HMT, Ferigolo One thousand. Dropout prevalence and associated factors in randomized clinical trials of adolescents treated for depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2017;39(5):971–92.

-

Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Cox GR, Simmons MB, Merry SN. Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:259–68.

-

Gujral S, Aizenstein H, Reynolds CF 3rd, Butters MA, Erickson KI. Do effects on depression: possible neural mechanisms. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;49:ii–10.

-

Cui DX. Effects of swimming exercise on neuroendocrine and behavior in experimental depression rats. East China Normal University. 2005.

-

de Castro JM, Duncan G. Operantly conditioned running: furnishings on encephalon catecholamine concentrations and receptor densities in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23:495–500.

-

Du Y, Wang L, Zhang XL, et al. A controlled study on the effects of practise on depression symptoms, cognitive function and γ-aminobutyric acid. Chin Gen Pract. 2019;17(9):1547–50.

-

Peng W, Chen Z, Yin L, Jia Z, Gong Q. Essential brain structural alterations in major depressive disorder: a voxel-wise meta-assay on starting time episode, medication-naive patients. J Affect Disord. 2016;199(14):114–23.

-

Matura South, Fleckenstein J, Deichmann R, Engeroff T, Füzéki Eastward, Hattingen E, Hellweg R, Lienerth B, Pilatus U, Schwarz S, Tesky VA, Vogt L, Banzer West, Pantel J. Effects of aerobic exercise on brain metabolism and greyness matter volume in older adults: results of the randomised controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;seven:1172–9.

-

Levy MJF, Boulle F, Steinbusch HW, van den Hove DLA, Kenis Chiliad, Lanfumey 50. Neurotrophic factors and neuroplasticity pathways in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:2195–220.

-

Himi N, Takahashi H, Okabe N, Nakamura E, Shiromoto T, Narita M, Koga T, Miyamoto O. Exercise in the early stage later stroke enhances hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and retentivity function recovery. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;257:132–41.

-

Mihailova S, Ivanova-Genova E, Lukanov T, Stoyanova V, Milanova Five, Naumova Eastward. A study of TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-10, IL-6, and IFN-γ cistron polymorphisms in patients with depression. J Neuroimmunol. 2016;293:123–eight.

-

Wegner Yard, Helmich I, Machado S, Nardi AE, Arias-Carrion O, Budde H. Effects of exercise on anxiety and depression disorders: review of meta- analyses and neurobiological mechanisms. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13(6):1002–14.

-

Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Archer T. Physical practise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(2):259–72.

-

Rebar AL, Stanton R, Geard D, Short C, Duncan MJ, Vandelanotte C. A meta-meta-analysis of the upshot of physical activity on low and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):366–78.

-

Knubben M, Reischies FM, Adli M, Schlattmann P, Bauer M, Dimeo F. A randomised, controlled report on the effects of a short-term endurance training programme in patients with major depression. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(ane):29.

-

Krogh J, Saltin B, Gluud C, Nordentoft Thousand. The DEMO trial: a randomized, parallel-group, observer-blinded clinical trial of force versus aerobic versus relaxation grooming for patients with balmy to moderate depression. J Clin Psychiat. 2009;70(vi):790.

-

Knapen J, Vancampfort D, Moriën Y, Marchal Y. Exercise therapy improves both mental and concrete wellness in patients with major depression. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(16):1490–five.

-

Machaczek KK, Allmark P, Goyder E, Grant Grand, Ricketts T, Pollard Due north, Booth A, Harrop D, de la Haye S, Collins G, Light-green G. A scoping written report of interventions to increase the uptake of physical activity (PA) amongst individuals with mild-to-moderate low (MMD). BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):392.

-

Stratmann M, Konrad C, Kugel H, Krug A, Schöning South, Ohrmann P, Uhlmann C, Postert C, Suslow T, Heindel Westward, Arolt 5, Kircher T, Dannlowski U. Insular and hippocampal greyness matter volume reductions in patients with major depressive disorder. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):102–fifteen.

-

Wood C, Angus C, Pretty J, Sandercock G, Barton J. A randomised command trial of physical activeness in a perceived environment on self-esteem and mood in UK adolescents. Int J Environ Health Res. 2013;23(4):311–20.

-

Jaffery A, Edwards MK, Loprinzi PD. Randomized control intervention evaluating the effects of acute practise on depression and mood profile: solomon experimental design. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):480–1.

-

Thomas AG, Dennis A, Rawlings NB, Stagg CJ, Matthews 50, Morris One thousand, Kolind SH, Foxley South, Jenkinson M, Nichols TE, Dawes H, Bandettini PA, Johansen-Berg H. Multi-modal characterization of rapid anterior hippocampal volume increment associated with aerobic exercise. Neuroimage. 2016;131:162–70.

-

Gutin B, Barbeau P, Owens S, et al. Effects of practise intensity on cardiovascular fettle, full body composition, and visceral adiposity of obese adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(5):818.

-

Gordon BA, Knapman LM, Lubitz 50. Graduated exercise training and progressive resistance training in adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled airplane pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(12):1072–9.

-

Mayer JS, Hees K, Medda J, et al. Vivid calorie-free therapy versus physical exercise to prevent co-morbid depression and obesity in adolescents and young adults with attending-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;nineteen(1):140.

-

Perri MG, Anton SD, Durning PE, et al. Adherence to exercise prescriptions: effects of prescribing moderate versus higher levels of intensity and frequency. Health Psychol. 2002;21(5):452–viii.

-

Zhang J, Chen T. Effect of aerobic practise on cognitive function and symptoms in patients with low. Natl Acad Sci Lett. 2019;42(5):419–21.

-

Fernandez AM, Torres-Alemán I. The many faces of insulin-like peptide signalling in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(4):225.

-

Piepmeier AT, Etnier JL, Wideman L, Berry NT, Kincaid Z, Weaver MA. A preliminary investigation of acute practise intensity on retentiveness and BDNF isoform concentrations. Eur J Sport Sci. 2020;20(6):819–30.

-

Deslandes A, Moraes H, Ferreira C, Veiga H, Silveira H, Mouta R, Pompeu FA, Coutinho ES, Laks J. Practice and mental wellness: many reasons to motion. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59(4):191–viii.

-

Carter T, Morres I, Repper J, et al. Practise for adolescents with depression: valued aspects and perceived change. J Psychiatr Ment Wellness Nurs. 2016;23:37–44.

-

Max O, Nicola Grand, Heidrun-Lioba Due west, et al. Effects of a 6-week, whole-body vibration forcefulness-training on low symptoms, endocrinological and neurobiological parameters in adolescent inpatients experiencing a major depressive episode (the "Balancing Vibrations Study"): study protocol for a ra. Trials. 2018;19(1):347.

-

Mello AF, Juruena MF, Pariante CM, et al. Low and stress: is there an endophenotype? Braz J Psychiatry. 2007;29(Suppl1(ane)):13–8.

-

Weaver LL, Darragh AR. Systematic review of yoga interventions for anxiety reduction among children and adolescents. Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69(vi):152–63.

-

Park CL, Finkelstein-Fox L, Groessl EJ, Elwy AR, Lee SY. Exploring how different types of yoga alter psychological resources and emotional well-existence across a single session. Complement Ther Med. 2020;49(2):102–fourteen.

-

Frank JL, Bose B, Schrobenhauser-Clonan A. Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health, stress coping strategies, and attitudes toward violence: findings from a high-hazard sample. J Appl Sch Psychol. 2014;30(1):29–49.

-

Wilson AM, Marchesiello K, Khalsa SBS. Perceived benefits of kripalu yoga classes in various and underserved populations. Int J Yoga Therap. 2008;18(ane):65–71.

-

Trent NL, Borden Southward, Miraglia M. Improvements in psychological and occupational well-existence post-obit a brief yoga-based program for education professionals. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8(3):21–vii.

-

Conboy LA, Noggle JJ, Frey JL, Kudesia RS, Khalsa SB. Qualitative evaluation of a high school yoga program: feasibility and perceived benefits. Explore. 2013;9(three):171–lxxx.

-

James-Palmer A, Anderson EZ, Zucker L, et al. Yoga as an intervention for the reduction of symptoms of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:78.

-

Hendriks T, de Jong J, Cramer H. The effects of yoga on positive mental health among healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2017;8:175–86.

-

Chen P, Wang D, Shen H. Physical activity and health in Chinese children and adolescents: skilful consensus statement (2020). Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(22):1321–31.

-

Stanton R, Reaburn P. Practice and the handling of depression: a review of the exercise program variables. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(2):177–82.

-

Tremblay MS, Kho ME, Tricco Ac, Duggan M. Process description and evaluation of Canadian Concrete Activeness Guidelines development. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010;vii(ane):42.

-

Roeh A, Kirchner SK, Malchow B, Maurus I, Schmitt A, Falkai P, Hasan A. Low in somatic disorders: is in that location a beneficial upshot of exercise? Front Psychiatry. 2019;ten:141.

-

Shiota N, Narikiyo Chiliad, Masuda A, Aou S. H2o spray-induced grooming is negatively correlated with depressive behavior in the forced swimming test in rats. J Physiol Sci. 2016;66(3):265–73.

-

Beserra AHN, Kameda P, Deslandes AC, Schuch FB, Laks J, Moraes HS. Can concrete practice modulate cortisol level in subjects with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2018;40(4):360–8.

-

Perraton LG, Kumar South, Machotka Z. Exercise parameters in the treatment of clinical depression: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(3):597–604.

-

Symons Downs D, Brutal JS, DiNallo JM. Self-determined to practise? Leisure-time exercise behavior, practise motivation, and practice dependence in youth. J Phys Deed Wellness. 2013;10(2):176–84.

-

Carneiro L, Afonso J, Ramirez-Campillo R, Murawska-Ciałowciz Eastward, Marques A, Clemente FM. The effects of exclusively resistance training-based supervised programs in people with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(xviii):6715.

-

Zhu XT, Ren YC, Feng Fifty, et al. Application of exercise intervention in the treatment of depression (review). Chin Ment Wellness J. 2021;35(i):26–31.

-

Pojednic RM, Polak R, Arnstein F, Kennedy MA, Bantham A, Phillips EM. Practise patterns, counseling and promotion of physical activity past sports medicine physicians. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(ii):123.

-

Morikawa R, Kubota N, Amemiya S, Nishijima T, Kita I. Interaction between intensity and elapsing of acute exercise on neuronal activeness associated with depression-related behavior in rats. J Physiol Sci. 2021;71(1):1–11.

-

Ross RE, Saladin ME, George MS, Gregory CM. High-intensity aerobic exercise acutely increases encephalon-derived neurotrophic factor. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(8):1698–709.

-

Grabovac I, Stefanac S, Smith Fifty, Haider S, Cao C, Jackson SE, Dorner TE, Waldhoer T, Rieder A, Yang L. Association of low symptoms with receipt of healthcare provider communication on physical activity amongst US adults. J Touch on Disord. 2019;viii:262–9.

-

Callaghan P, Khalil E, Morres I, Carter T. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of preferred intensity practise in women living with low. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:159–68.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros thank all of the staff who contributed their time to our enquiry.

Funding

This work was supported past the Key Laboratory Project of Shanghai Science and Engineering Commission (11DZ2261100).

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

XW and XW conceived and designed the study, Z-dC and Westward-tJ analyzed the data, Y-yF and W-xS were major contributors to writing the manuscript. All authors contributed sufficiently to this piece of work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Consent for publication

All authors agreed the possible publication of our article on Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. The participant has consented to the submission of the commodity to the journal.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of involvement.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long as you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables licence, and point if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this commodity are included in the article's Artistic Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If textile is non included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended utilize is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nix/ane.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Wang, Ten., Cai, Zd., Jiang, Wt. et al. Systematic review and meta-assay of the furnishings of exercise on depression in adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 16, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s13034-022-00453-two

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s13034-022-00453-2

Keywords

- Exercise

- Boyish

- Depression

- Depressive symptoms

- Meta-analysis

- Systematic review

Source: https://capmh.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13034-022-00453-2

Post a Comment for "Peer Reviewed Articles the Effects of Exercise on Depression"